They brought to the Pharisees the man who had formerly been blind. Now it was a sabbath day when Jesus made the mud and opened his eyes. Then the Pharisees also began to ask him how he had received his sight. He said to them, “He put mud on my eyes. Then I washed, and now I see.” Some of the Pharisees said, “This man is not from God, for he does not observe the sabbath.” But others said, “How can a man who is a sinner perform such signs?” And they were divided. So they said again to the blind man, “What do you say about him? It was your eyes he opened.” He said, “He is a prophet.” [John’s Gospel 9.13-18]

A few weeks ago, a church leader sat with Jesus in the dark, talking (spiritual) obstetrics. The Spirit breathes where it wants. Just last week, a foreign woman shared a midday drink with Jesus, talking about water which quenches thirst forever. The Spirit breathes where it wants.

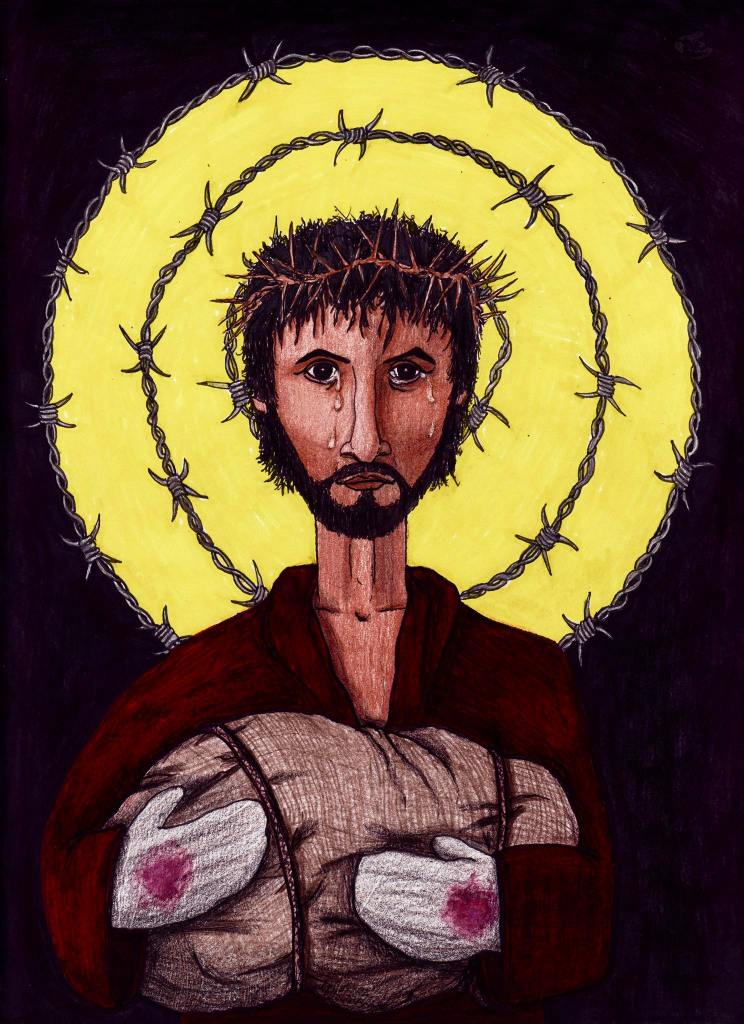

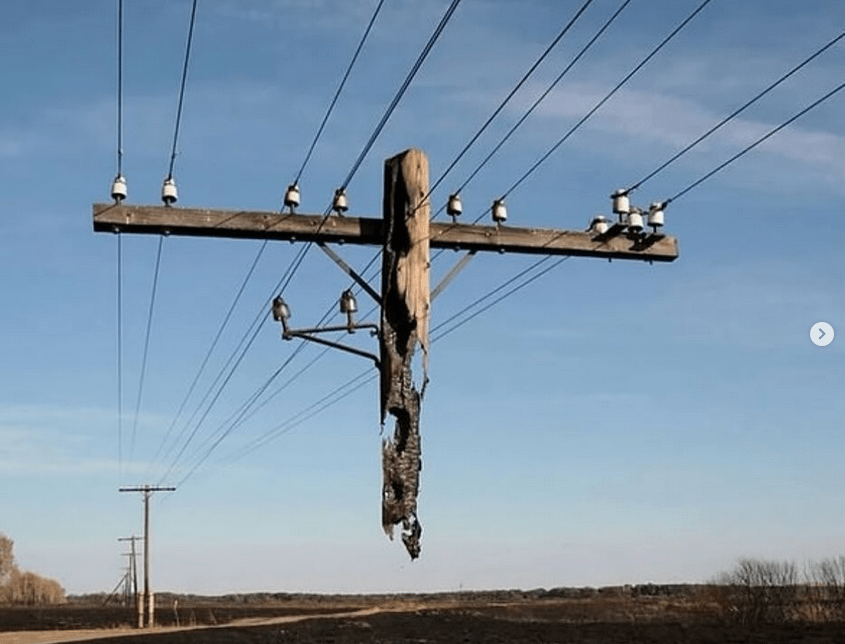

A man, sitting always in his individual darkness, is suddenly able to see. The Spirit breathes … and people of faith erupt. This in the wrong day. What poor theology. Something, everything is wrong – wrong day, wrong man, wrong act, wrong answer. There must be someone to blame, to punish, to banish, to deny.

We read this story, and watch it unfold. We wonder how anyone, any community, could act in this way. Then we walk past a mirror, and stumble. All too easily we can locate our face in the crowd, and perhaps even hear our voice.

A gift is given. A life enhanced. One translation uses the phrase, “The Spirit respires where it will”, as if the breathing, the respiration, of the receiver is eased by Jesus’ presence.

Yet, for an awful moment, all the air is sucked out of the room by the indignation of the community of faith. There are rules. The Sabbath is not for healing.

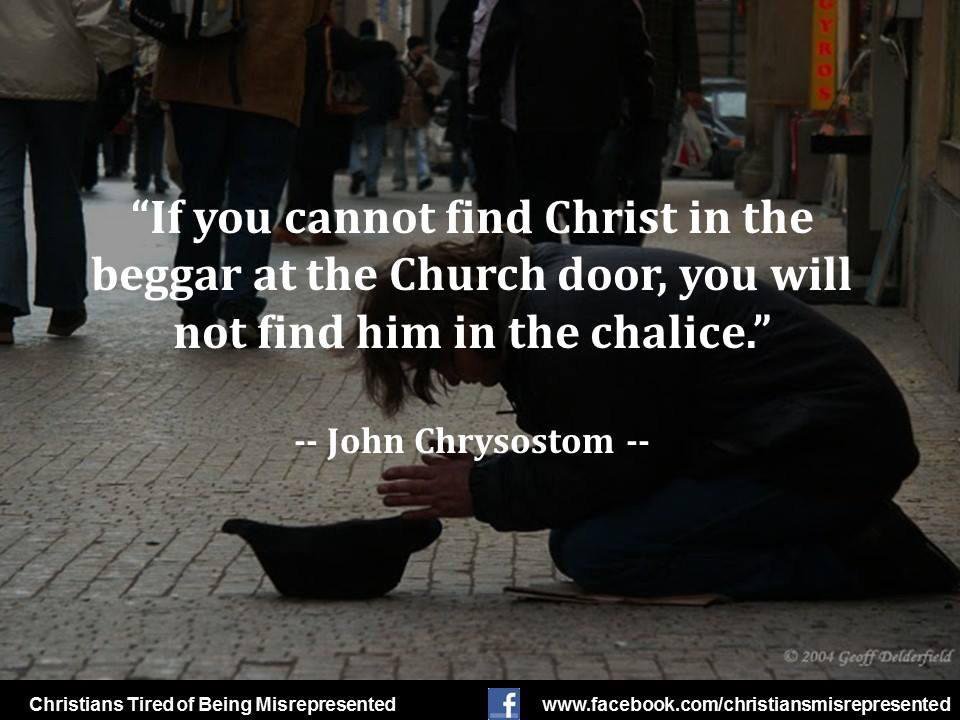

You can’t just feed someone because they are hungry.

There’s a queue, they have to start at the back.

What if she was asking for it?

The risk of these gospel stories is finding ourselves within them. We hope to imagine ourselves as the one receiving life, and that may well be our experience. We may also find ourselves mingling with those offering judgement, not justice; blame, not blessing.

These narratives of respiration disrupt our faith and our lives. When someone is offered life, it is disturbing for everyone they meet. When a person is offered forgiveness, when people discover mercy, they become entirely different.

There is, however, a profound danger in forgetting. When we forget the wonder of our first respiration; when we misremember what mercy is all about; when we only recall the culture which constrains us and not the Spirit who breathes us life.

When we forget what it is to see again.

This church leader, this foreign woman, this formerly blind man are all offered mercy and life for the circumstances in which they find themselves. Perhaps they, or their families, are members of John’s community, to remind us so that we, in turn, are able to remember.

Our remembering is never solely for ourselves, but for the one who comes to us at midnight, or midday, or in their own personal darkness. Jesus never turns us away.

The Spirit breathes where it wants. May you hear the sound of it.