“But I say to you that listen, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you,bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you.If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt… Do to others as you would have them do to you. [Luke’s Gospel 6.27-31]

There is a voice growing in the life of the Church, which has been almost silent, or perhaps silenced, for some time.

Some of the fault lies with us, as we have sought to regain credibility with the community around us and sought to understand how to live – and speak – the Gospel in a changing world.

We have also been cautious about comparing politicians and other leaders with the miscreants of the past; the argument is already lost when you invoke the tyrants from days gone by. So, we have learnt either to speak in whispers, or not all. As always, some church leaders have simply fallen into line, finding black and white answers appealing, or laying blame at the door of those who are most easily attacked.

The growing voice is evident in the United States, as punishment after punishment falls upon those least able to bear them. Most recently, the Roman Catholic Bishop of El Paso, Mark Seitz, called the treatment of undocumented immigrants a “calumny”, as they can no longer seek sanctuary in hospitals and churches.

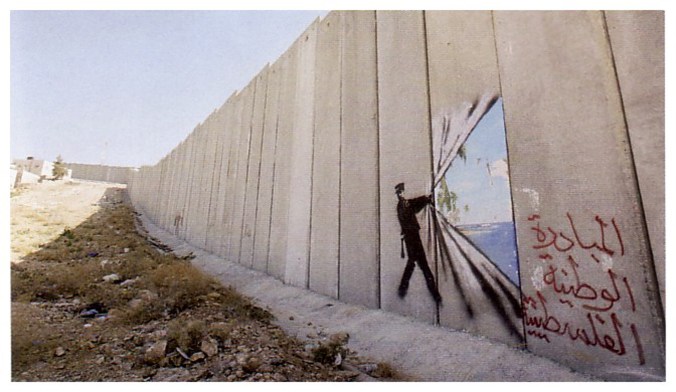

People of faith in Australia have acknowledged the increasing anti-Semitic attacks, while, at the same time opposing the violence directed against the Arab and Muslim community. The church has found the capacity to articulate nuanced support for all those in need, not neglecting to challenge the Israeli invasion of Gaza and the West Bank over the last several years, while opposing the political violence of Hamas.

An essential rule is that if someone tells you the answer is simple, be suspicious.

When Jesus offers the Sermon on the Plain, this is not spoken in a churchified bubble, but in the midst of a community under an empire’s heel and the recreant monarchy of Herod. The enemies who strike, hate and curse are most commonly the soldiers of Rome, rather than the person who votes differently, or blames others for the way the world is.

These words of Jesus have as much resonance now as they did two millennia ago, calling us to live in such a way that our community is confronted and, hopefully, blessed. Many of these commands have echoes in other parts of scripture, and other faith communities; there is one, however. which stands out.

“Love your enemies”. How, on earth, is this possible? And yet, Jesus commands the community into this place.

This is not a command to stay with an abusive partner, neither does it ever seek to diminish the suffering some people endure, nor does it see forgiveness as avoiding accountability and justice. People need to be safe.

It does call us – as a community, supporting each other – to so radically understand what it means to be followers of Jesus, that everything turns upside down.

We love our neighbour and our enemy, while offering a voice for those who cannot speak for themselves. We love those who seek to harm us and provide refuge for those who have already been abused. We give to those who take from us, ensuring that food and clothing are already in the hands of those who are hungry for justice and bread.

What will mark us as followers of Jesus? Falling into line with community and government, or offering mercy and love to those who may never love us back?