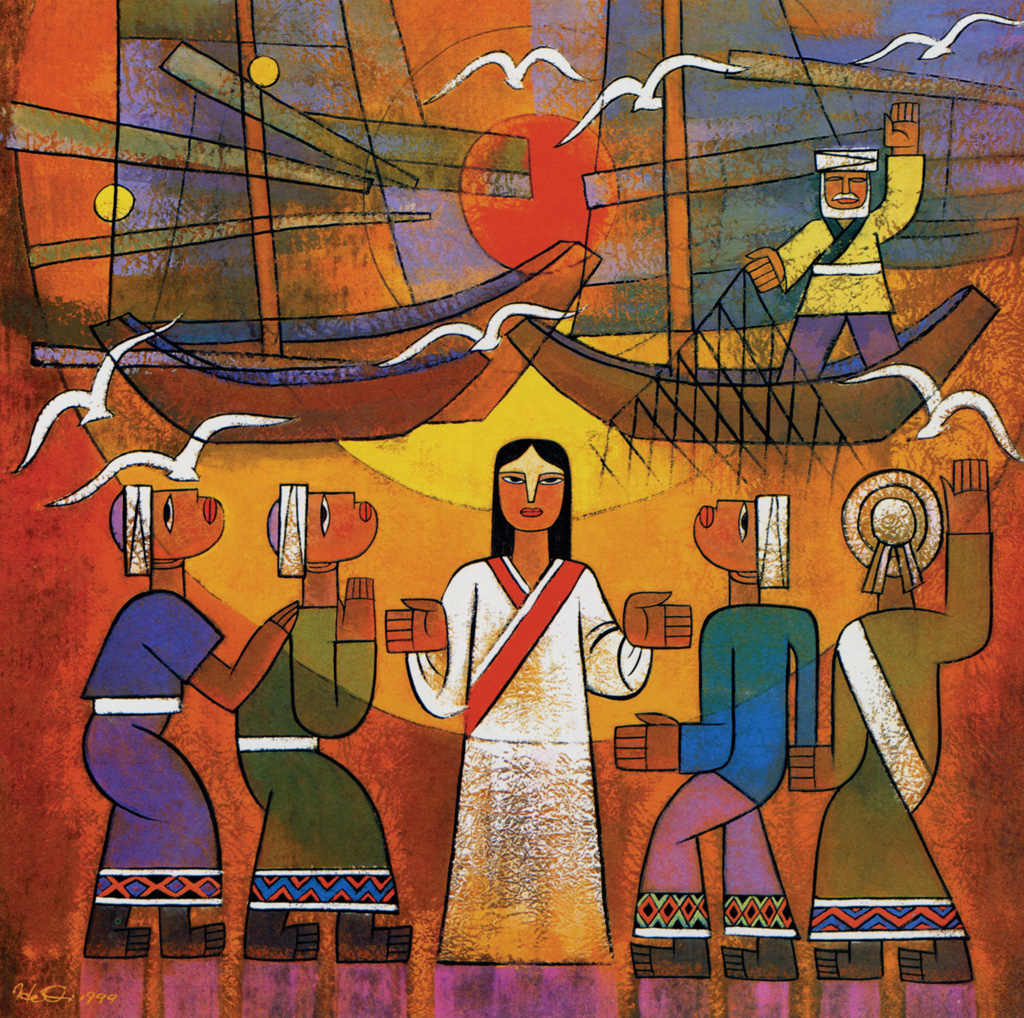

Just then his disciples came. They were astonished that he was speaking with a woman, but no one said, “What do you want?” or, “Why are you speaking with her?”Then the woman left her water jar and went back to the city. She said to the people,“Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah, can he?” They left the city and were on their way to him. [from the Gospel of John 4.4-42]

The darting poetry of this conversation, John’s narrative, as this woman and this man engage with each other in the heat of the day. Image and metaphor, question and reframing, step and dance; two thirsty people.

It could almost seem whimsical, even allowing for the context of her apparent social marginalisation and his presence in the wrong territory. With the wrong person.

Notwithstanding, she does not shy away, even at the cultural baldness of his request … demand. The conversation moves through theology and need, to theology again. Claim and counter claim, as sibling cultures engage, working themselves out in the midday sun.

Perhaps she serves him. Perhaps they each imbibe the well’s gift. Perhaps they are equally blessed to have their thirst relieved.

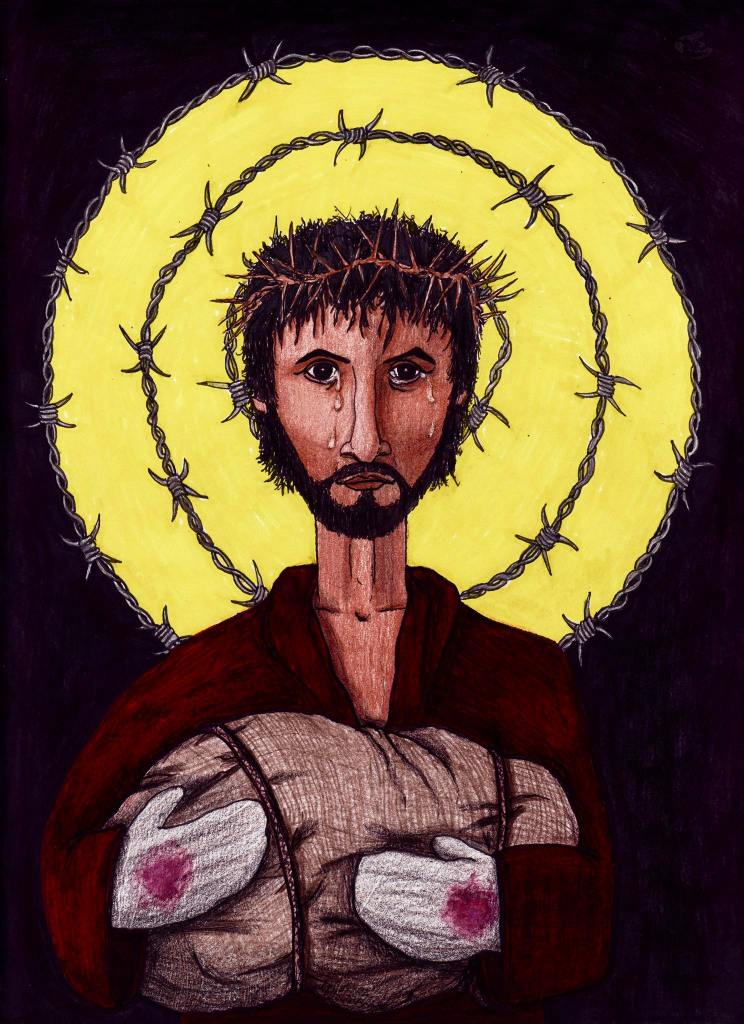

At what appears to be the utter end of everything, he will be thirsty again. Sour wine must suffice on that occasion, stuttering heartbeats from his final breath. Perhaps one of the faithful women there held it to his lips?

And then the (potentially hazardous) blessing of knowing. And being known. She has hidden here because the journey of being known has proved all too costly. Yet here is the profound gift he proffers her.

A man who told me everything I have ever done. Then the words, unspoken, yet clear as midday sun, and still he offered me life!

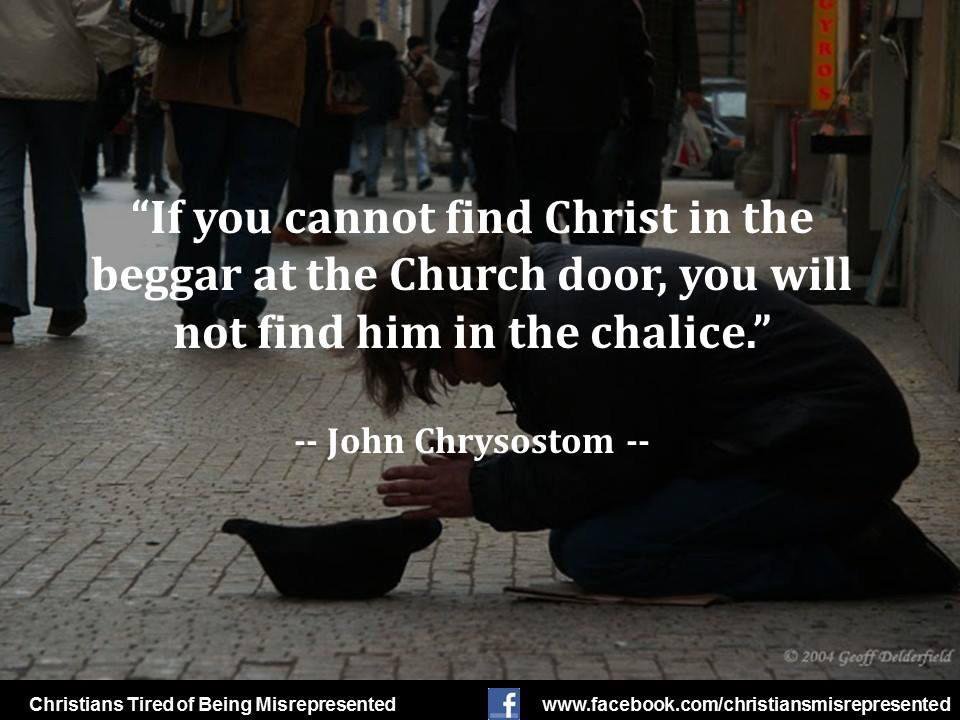

This encounter, beyond theology and culture, claim and counter-claim. When we are told (and even believe) that we have no name, no faith, no future, no place but the margins, no worth but our failure, he meets us where we are, he asks us for help, and he offers us life.

He knows all our story, and loves us, this Jesus.

Nothing will prevent Jesus’ offer of life, to each and all of us. Always.

A Drink of Water | Seamus Heaney

She came every morning to draw water

Like an old bat staggering up the field:

The pump’s whooping cough, the bucket’s clatter

And slow diminuendo as it filled,

Announced her. I recall

Her grey apron, the pocked white enamel

Of the brimming bucket, and the treble

Creak of her voice like the pump’s handle.

Nights when a full moon lifted past her gable

It fell back through her window and would lie

Into the water set out on the table.

Where I have dipped to drink again, to be

Faithful to the admonishment of her cup,

Remember the Giver, fading off the lip.