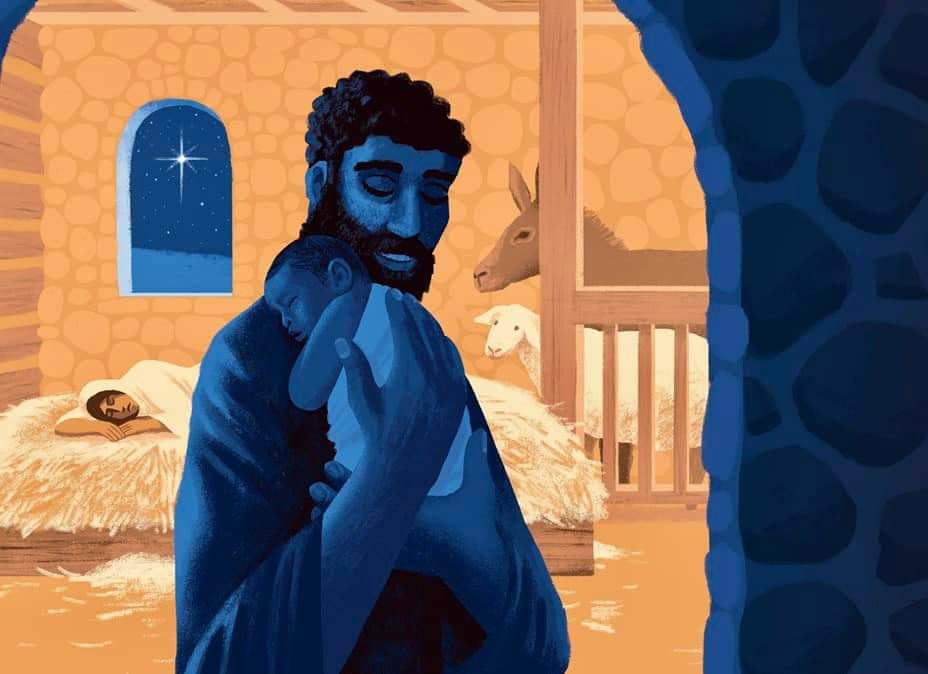

… Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white.Suddenly there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him.Then Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here; if you wish, I will make three dwellings here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud a voice said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell to the ground and were overcome by fear.But Jesus came and touched them, saying, “Get up and do not be afraid.” And when they looked up, they saw no one except Jesus himself alone. [from Matthew’s Gospel 17.1-9]

All those things which demand our time and our attention. These compelling events before us, which elicit the response of our action, or at least profound concern. Recent happenings leave us dumbfounded, unsure of which step to take, which words to say, what to feel.

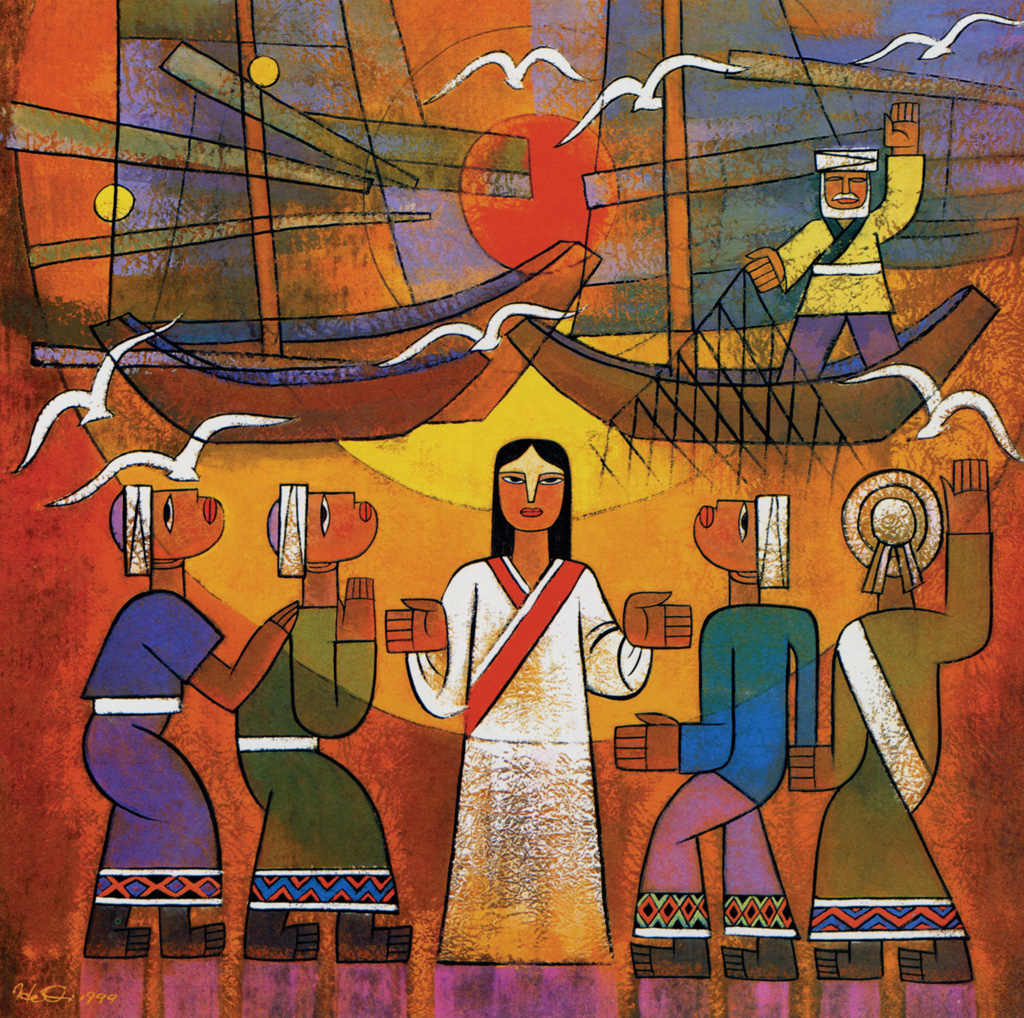

As followers of Jesus, we watch his interactions with many diverse people; storytelling, feeding, chastising, blessing, inspiring, forgiving, healing. These consistently human moments can distract – even mislead – us into engaging with Jesus solely as the astonishing person that we see and hear.

Jesus exhibits the joy and grief and anger and compassion of every fully human being. We are in his company, and his hands and feet and voice are like our own. We will achieve great things together.

We see the need and rally to the cause. The needs are many, the wounds are deep.

Those politicians and others who want us to discard God and despise our neighbours rely on our exhaustion and eventual despair. Worse, they want to curdle our passion into hatred – someone, something, any one or thing – enlisting us in their crippled cadre.

Which is why at the hinge of Jesus’ journey through Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus ascends a mountain with three friends. Which is why a moment described (and entirely beyond description) happens before their eyes.

God interrupts the plans and purposes of each of us, to remind us that Jesus is not only utterly human, but the beloved Son of God. We are frantic to contain the moment, posting it to Instagram, or its miserly equivalents. Before we are able to focus our cameras and our lives, we are in the presence of Jesus, alone.

It is simply Jesus, Son of God.

A moment of miracle and wonder, which healed no wounds and brought no justice, and which calls us to remember that Jesus is the story of God in the world. Peter has already felt Jesus’ reprimand, as he earlier sought to prescribe Jesus as warrior or monarch. We are reminded that on this journey we are following the One who suffers at our hands and whose life is given for the life of the broken world.

This is where our faith finds its bearings. We cannot defeat the systems which fashion evil and injustice, although we must speak and act for all those who cannot speak and act for themselves, or believe themselves alone. We require the guidance of God’s Spirit to navigate these paths and discern where stumblings and missteps are prevalent.

It is difficult not to be afraid.

We do not walk an untravelled road; Jesus is before us, and beside us. The saving of creation is utterly in the hands of God. It is for us to bear witness with our lives. Our hope is found in Jesus Christ, alone.