When they had finished breakfast, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon son of John, do you love me more than these?” He said to him, “Yes, Lord; you know that I love you.” Jesus said to him, “Feed my lambs.” [John’s Gospel 21.15]

It’s like déjà vu all over again.

Stories of disciples fishing, then the additional similarity of an empty catch, and the advice from a stranger. It’s an echo, or reflection of the start of Matthew, Mark and Luke’s Gospels; we can hear the tune of the old Sunday School song in our ears, when Jesus called the disciples to leave their nets and follow.

We are here, at the close of John’s Gospel, hearing their beginning, at the end.

Have the disciples lost their faith, lost their hope, or are they simply lost? A heartbeat ago, they were embraced in peace and purpose by Jesus’ blessing and the Holy Spirit. Now they have returned to what they used to know, perhaps fishing for a meal, or they are not sure who they are without Jesus.

However, the net remains stubbornly empty; have they forgotten even this?

It may well be that John’s last chapter is necessary because Peter is not yet sure who he is in the light of Christ’s resurrection. Mary’s fear has been addressed, as has Thomas’ faithful doubting.

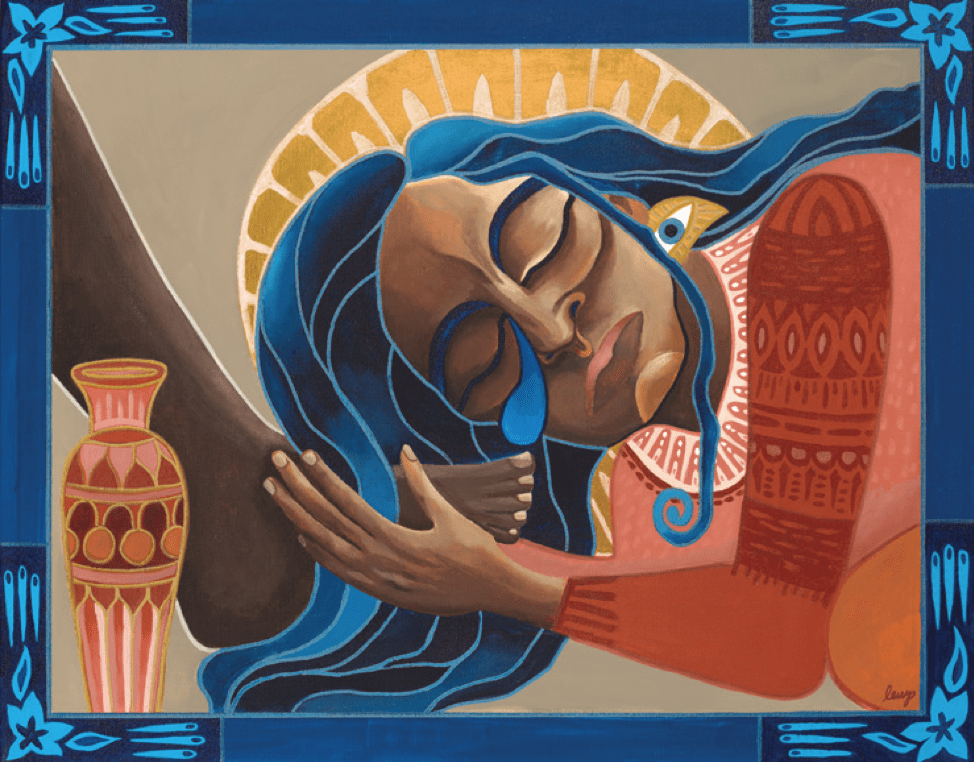

Peter has not yet been reconciled with himself and Christ.

Jesus searches him, and knows him; he hems Peter in, behind and before, and will not let him go. Peter’s three earlier denials, punctuated by the rooster’s crow, require Jesus’ three questions framed in love and purpose. This is more demanding than forgiveness, more profound than reconciliation; this is a new creation in evidence.

“If you love me more than these, then look after my flock.” As you grow, events will become more challenging, more onerous, and your life will draw to an end in a manner beyond your choice. So, follow me.

No nostalgia in evidence, no Sunday School chorus playing in the background; this is the consequence of resurrection. This is what disciples do. This is who disciples are.

Until this moment, it is possible we imagined resurrection was simply an extraordinary miracle, offering life. Peter has discovered that it changes our lives, as an echo of the creation’s very renewal.

Wonder, absolutely. Life, without a doubt. Forgiveness and mercy, beyond measure.

For Peter, and thus, for us? To be the disciples of a risen, crucified Lord, who will recreate and renew humanity as his own, and who calls us to follow him from the beginning, until the creation is complete, when “all is unentangled, all is undismayed.”