Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.” Pilate asked him, “What is truth?” [John’s Gospel 18.37-38]

This week new laws are being introduced to Federal Parliament about the misuse, abuse and proper use of social media for younger people.

This legislation arises from any number of causes, many of which you will have discovered for yourself, or know their harm within your own family, or amongst your friends and those for whom they care. Bullying, abuse and misrepresentation have always been present in the world around us, but suddenly they have become more constant, more present and, seemingly, more pernicious than ever before.

At its reasoned best, arising from real concern, this is an attempt by my generation to offer safe haven to our children and grandchildren. We will see, after the all the political compromise, whether a camel emerges, and whether it has any remaining breath.

I doubt that today’s media and social media influencers and manipulators are worse characters than the propagandists of generations past; the fabrications of politicians in our parliaments are, perhaps, simply less subtle than those who tarnished nations two decades, two centuries, or two millennia ago.

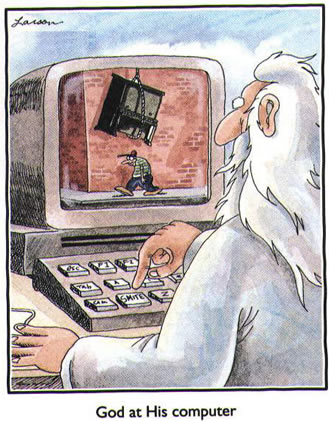

Our deep suspicion, even fear, of artificial intelligence has a rational justification; things are frequently not as they appear. That image, that quote, that video are simply not real. Black might now appear as white.

In a social climate where people believe that fewer and fewer things are able to be “proved”, when suspicion and disbelief are easily ignited, what shall we offer?

If I could just convince you, with further proofs, or a better argument, or a clever turn of phrase. I might be tempted to ridicule your thinking, or point out the weaknesses in your argument, or simply make you feel a fool. Then you’ll change your mind.

In his exchange with Pilate, as he faces his own punishment and death, Jesus talks about truth. He has been mispresented, trolled, and lies about him have been going viral. He is moments away from the cross.

Jesus declares his purpose, to testify to the truth. The word he uses is where our word for “martyr” originates; Jesus bears witness with his own body. His clearest declaration, which has lasted two thousand years, is on the cross – a broken body for a broken world.

Our task is not to win every argument and ridicule those who can’t agree. We are called to bear witness with our lives, so that the truth of what we say is realised because it is amplified – and verified – by how we live.

Mercy remains a meme until we offer it; compassion and forgiveness and hope are only words until our lives make them tangible. And when we offer bread to the hungry, we may just receive their permission to speak of when our hunger was met by Jesus.

What is truth? It is found in Jesus Christ, crucified and risen.