Bartimaeus began to shout out and say, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” Many sternly ordered him to be quiet, but he cried out even more loudly, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” Jesus stood still and said, “Call him here.” And they called the blind man, saying to him, “Take heart; get up, he is calling you.” So throwing off his cloak, he sprang up and came to Jesus. [Mark’s Gospel 10.47-50]

An argument can be made that the Harry Potter books are, essentially, not about magic at all. All the palaver from a few groups in our community about witches, wizards and wands – and the banning of books – meant that a handful of people missed the story entirely.

A engaging story of the journey through high school and adolescence was wonderfully about courage and grief, teenage humour and discovery, fear and love and laughter, the making of friends and the hope of a future after significant loss. The magic, for most of the story, was icing on the cake.

A similar argument can be made about Bartimaeus and his encounter with Jesus – that it’s precisely not about fixing the sight of a blind man. An extraordinary series of gospel stories culminates in this man seeing more clearly than anyone else. The irony is that almost no one notices him, ever. The irony, magnified, is that his physical vision is almost entirely impaired.

Mark builds the story carefully, with the disciples walking, stumble by misstep, after Jesus.

A foreign woman, least expected to understand the mission of Jesus because of her gender and being a gentile, redefines his calling through desperation and hope. In the next breath, children are welcomed by Jesus, as he declares their perspective as most appropriate to comprehend God’s reign.

The disciples, and the crowd of which we are a part, are amazed when a rich man rejects Jesus’ invitation and challenge, and again when the Pharisees see their task as stumbling blocks as opposed to stepping stones. How is it possible that the rich and the clergy fail to understand Jesus’ call to discipleship?

Thus we meet Bartimaeus, who sees clearly enough to defy the crowd. The rich man was unable to leave everything behind; Bartimaeus walks away from his livelihood in order to discover life. The Pharisees laid traps for Jesus and Bartimaeus evades them all as he walks from a beggar’s life to discipleship.

Jesus asks James and John the identical question that he asks Bartimaeus. The brothers request glory, greatness and recognition. Bartimaeus asks for mercy.

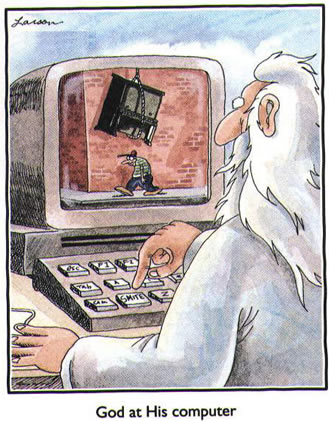

When we read this story, the culmination of this stanza in Mark’s Gospel, do not miss the meaning by looking only for the illustrations.

When we encounter Jesus, despite all the obstacles we have overcome, what do we need to ask him? And what, in mercy, do you believe Jesus will say?